Research in the Time of Coronavirus

How do historians perform research during a global pandemic? During these confusing times, Dr. Maria Americo, Assistant Professor of History, has written an open letter to budding historians to talk about her ongoing research during a time of national crisis. Dr. Americo specializes in Classical studies, Islamic studies, and the Ancient Mediterranean World.

Dear current & future historians,

First off, I hope that you and your families are all well, and that you have everything you need. I am well, but I miss our academic community very much. As you all know, nearly every activity that jam-packed our busy modern lives just one month ago has now been canceled, postponed, or changed in unprecedented and irrevocable ways. The place where our work, studies, and daily lives intersected—Saint Peter’s University, Hilsdorf 3rd floor, and all our other buildings that dot either side of JFK Boulevard—with so much laughter, fun, discussion, debate, and learning has moved online. We are all doing our best, and I am impressed by the hard work and resilient hope of our students, faculty, staff, and administrators every day.

So: if college courses are online, work meetings have gone digital, news reporters broadcast from their homes, we video chat with friends and family, and I now take and teach dance classes in my living room(!), does scholarly research also still exist?

Well… kind of. Historians like me, who work on premodern history, are heavily dependent for their research needs upon the libraries, with their collections of thousands of real, tangible, physical, glorious old books, with two covers, pages, and a spine. (Remember those? I sure miss books!) As I’m sure you know, many libraries worldwide are now closed. But aren’t books online? Yes, some books exist as digital resources. But much of my material has not been—and perhaps never will be—digitized. And so I patiently await the reopening of our libraries.

Just days before our local and federal government began to respond to the threat of this virus in a big way, I had agreed to begin work on two exciting academic research projects. One is a book proposal(!), which is still so much in its infancy that I think I’ll tell you more about it later. 😉

But the other is a contribution to the upcoming Encyclopedia of the Global Middle Ages, which is to be published by Bloomsbury. I’m told this is the same company that published the Harry Potter series (…I must be the only millennial alive who has never read those books, though students tell me I should all the time!), so it’s exciting to see them move further into the academic space. Since this encyclopedia will focus on the global Middle Ages (which many of you know is right up my alley!), the editors are seeking articles that describe the ways in which cultures connected during the medieval world.

For this encyclopedia I have agreed to write two Object Histories on artworks that, through their physical existence and iconography, help tell the story of the interconnected global Middle Ages. And I know some of you will recognize one or both of them!:

- Bowl, Persia, 13th century, from the Met

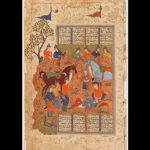

- Shahnameh manuscript folio, Persia, ca. 1600, from the Freer/Sackler

…And, if we were in class, you know what would happen next: we do the “art day thing” and explore what these objects can tell us about the global history of the Middle Ages. I won’t give you all the answers about these objects today (you’ll just have to read my articles when they come out!), but I will give you a few hints. First, take a look at the symbols around the rim of the bowl. If you look closely, I guarantee you will recognize them. Those 12 (hint, hint) symbols were just as globally recognizable in the year 1400 CE as they are today. By the time our bowl was created in the 13th century of our era, those symbols were already ancient; they were first conceived of sometime around 1000 BCE and spent the next two and a half millennia traveling all over the Old World. As I like to say in class, symbols persist.

If you were in my Medieval World class last semester, then I know you will recognize the manuscript folio on the right. This illuminated manuscript folio shows one of antiquity’s most famous people, Alexander the Great, appearing as a special guest in the medieval Persian epic poem the Book of Kings (Shahnameh). Why? My Medieval World students could tell you… or you could wait until the new encyclopedia comes out. More details will be forthcoming later.

As I sign off here, I want to remind you that we are living through history right now. Of course, we all live through, and create, history every single day. But that is truer now than ever. How will the historians of the future remember the year 2020? None of us can say for sure, but I hope that, when they look back at the SPU community at least, they will tell the story of how we stood for and with each other with understanding, love, compassion, and forgiveness. I close as I began: I hope you and your families are well, and that we can meet again face-to-face as soon as it is safe to do so.

All best, and stay well,

Prof A